- Home

- Aleksandra Ross

Don't Call the Wolf

Don't Call the Wolf Read online

Dedication

For Babi, who was Irena first

Contents

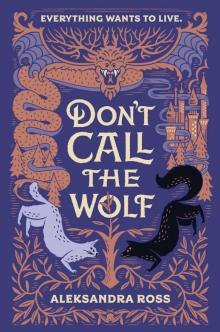

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Tadeusz

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Henryk

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Rafał

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Michał & Eliasz

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Eryk

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Anzelm

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Jarek

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Franciszek

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Epilogue

Pronunciation Guide

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Books by Aleksandra Ross

Back Ad

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

A WHITE CASTLE ONCE STOOD in the forest, with spires that soared to the lower floors of heaven and dungeons that stretched ever downward, or so the legend went, to brush the very chimney stacks of hell. To the villagers who prospered in its shadow, the castle encompassed the entire expanse of earthly life. Its mausoleums housed the bones of ancient lords, its throne bore up their beloved queen, and its crib cradled their tiny, treasured princess.

But then, the world grew dark.

Slowly at first. With small things, things that scuttled and slithered. In the treetops, nocnica danced on their spider legs and looked for humans to strangle. In the rivers, rusalki circled unsuspecting swimmers, whispering in their ears before they dragged them under. In the castle grounds, three hundred nawia glided across the lawn and left the smell of frost and rotting flesh. And within the castle itself, psotniki stumped across the marble floors, chuckling softly as they plucked the eyes out of sleeping nobles.

And then, gliding over the treetops, came a Golden Dragon.

They said, afterward, that its wings blocked out the sun. Formed of gold, it was like nothing they had ever seen. Some said it was the most beautiful, the most heavenly of monsters. Its claws were glass. Its teeth were crystals. Its eyes were so dark that in them, they said, was held the ruin of worlds.

With sunlight glancing off wings of gold, the Dragon took the castle spire in its claws. It ripped. It tore. The villagers came out from under their doorways and shielded their eyes. They watched as gold and fire blazed on the threshold of heaven. They watched, realizing too late what they saw, as in that topmost chamber, the Dragon devoured the young queen and her daughter. Too late the knights drew their swords. Too late they charged up the spiraled stairs. Too late they paused in the dim stone hallways and heard, far above them, the echo of glass claws on stone as the Dragon launched itself from the white walls. It flew east across the forest. And there, in the Moving Mountains, it made its roost and awaited the onslaught of knights.

And they came.

Heartbroken and furious, the king gathered his knights. Banners flying and swords chiming, they galloped down the drawbridge and through the dark woods.

One by one, they were picked off among the twisted trees. Many survived, only to be lost among the unforgiving Mountains. And of those who remained—those who conquered the Mountains, who eked out the hidden trails, who scaled its peaks, who outwitted its monsters—those who were battle-hardened, or brave, or talented—those last, doomed souls were crushed in golden jaws.

Below, the trees grew thicker. The villagers mourned. In a bid for the vacant throne, the more ambitious nobles put on old-fashioned armor and rode out to face the dragon and prove their worth. Not a single one of them returned.

The kings of other lands arrived. Some brought gold and silver. Some wielded chipped blades and rode scarred warhorses. Some employed magicians and soothsayers and made offerings to the saints of dragon slayers and kings. And when those kings were dead the armies came. Led by drummers and trumpeters, black-coated soldiers rode in military formation, sabers rattling and rifles primed. In all, within ten years of the Golden Dragon’s attack, ten thousand warriors crossed the borders into the forest. They were professionals, they were aristocrats, they were the civilized and the elite and they were men and women already living legends of their own.

They were not enough.

Ten thousand souls went into that forest, and ten thousand souls were lost.

In the end, the cleverest and the bravest were the people who fled. The ones who took what they could carry and ran and never looked back. The ones who abandoned fortune and birth and everything familiar and left the kingdom to the Dragon.

Of course, some stayed behind, and the dark things found them. For in the wake of the Dragon, these things grew braver.

Evil wrapped itself around the little village. Evil walked the crumbling streets, evil lurked between stuccoed buildings. It looked down from the rafters with glowing eyes. It rattled its claws in the corners. It strangled the villagers in their beds. It dragged them to the depths of rivers. It snatched them up on quiet roads. It beckoned from shadowed eaves. Evil sang to them in the dark, candles burning, nights eternal.

In time, the forest darkened. Its borders closed. For a long time, there was no hope.

And then, from the darkness, rose a queen.

1

“LADIES AND GENTLEMEN,” BEGAN PROFESSOR Damian Bieleć, “we live among legends.”

He paused, bracing his hands on the sides of the lectern.

“For we have lived through the fall of Kamieńa. We have lived through the advent of the Golden Dragon. And in the midst of both these tragedies”—Damian Bieleć’s voice fell to a carefully crafted whisper—“we have seen—nay, we have borne witness to—the last of the Wolf-Lords.”

A thrill ran through the auditorium. Shining heads bent toward one another. Their owners ignored the tight collars digging into throats as they murmured their admiration for a brilliant speaker, their interest in a fascinating subject. The air rustled with low voices, and Damian Bieleć waited before proceeding.

In the back of the auditorium, leaning against the doorframe, Lukasz put his hands in his pockets.

Outside, it was June. Outside, children were laughing, parents were scolding, and carriages were clattering. The streets were filled with fire breathers and ice-cream vendors. Outside, the world was a riot of summer and sales, of bartering and bickering. Miasto was the greatest city in the world, and it was at its peak. But in here, in this moment, no one cared about the outsi

de.

Because in here, in this ageless dim, legends were being told.

“For a thousand years, the Wolf-Lords did not leave the Moving Mountains,” Professor Bieleć went on. He inhaled deeply, nostrils flaring, as if he could actually smell the cold shale and hot smoke of that lost world. Then he said: “Until seventeen years ago.”

Another pause.

“Until the Golden Dragon.”

His listeners were on edge. Lukasz could feel it. He could also see it, betrayed in the glances cast over shoulders, in the subtle twitches of those elegant faces. It was half fear, half hope. Maybe they had even come for the same reason as Lukasz had: Not just to listen to fairy tales, not just to learn of the Wolf-Lords. But to see for themselves whether the gossip rags were true.

Whether there really was, somewhere in these hallowed halls, an Apofys dragon on the loose.

“For ten centuries,” Bieleć was saying, “the Wolf-Lords lived in isolation and in a state of barbarism that we can only imagine. They carved out niches among the shifting rocks and weathered the tides of those Mountains. They hunted dragons and made blood pacts with wolves.”

Somewhere near the front of the auditorium, a projector rattled to life. A map of Welona loomed, with the ocean to the north and Miasto—where they were now—marked by a star in the south. To the northeast, a black stain marked the kingdom of Kamieńa. And still farther east, beyond the forest, a line of crosshatching represented the vast, legendary Moving Mountains. A Dragon, rendered in golden ink, wrapped golden claws around forest and mountain.

There were sounds of awe from the audience.

“Because seventeen years ago, the Golden Dragon attacked the kingdom of Kamieńa,” recounted Professor Bieleć. “And shortly thereafter, the Wolf-Lords left the Moving Mountains. Were they pushed out by the dragon, which had claimed their ancestral home as its roost? Or were these dragon slayers as foolish as the king of Kamieńa, and were they, too, killed in its pursuit?”

He chuckled, and Lukasz cracked his knuckles. Ironic, he thought. Bieleć wanted to criticize Wolf-Lords when there was an Apofys running amok upstairs?

“But all we know,” Bieleć murmured, lowering his voice, “is this: In the end, only ten Wolf-Lords remained. Only ten came down from the Mountains.”

The map trembled in place for a moment. Then Bieleć made a small signal, and the slide changed, the projected image shuttering up and out of sight. A photograph took its place, black pigment stained brown with age.

“These ten men were the Brothers Smokówi.”

The photograph had been taken from a distance, with a low line of black trees cutting a stark line in the background. In the foreground, ten men were seated on black warhorses. Nine of the ten horses each had a set of antlers on their bridles: some ending in elegant curls, others simple and spiked. The men had serious faces. They wore leather and fur.

They looked, in a word, barbaric.

“These ten,” whispered Damian Bieleć, “became the Brygada Smoka.”

A crest ratcheted onto the screen: a wolf’s head, flanked by crossed antlers. Below the image ran lettering familiar enough that even Lukasz could recognize it.

ZĄB LUB PAZUR

“Tooth or claw,” translated Damian Bieleć. The projector’s beam cast his face in alternating light and shadow. “The motto of the Wolf-Lords. And later, the motto of the great Brygada Smoka.”

Lukasz placed a cigarette between his teeth and fished out his lighter. Almost reflexively, he ran his fingers over the case. He knew the etching by heart: crossed antlers and a wolf’s head.

When he looked up again, he could have sworn he saw Bieleć’s head twitch toward the lighter’s flash. The professor paused a split second before he resumed his talk.

“Their—their beginnings were modest enough.” He faltered. “The brothers began by hunting lesser dragons, collecting bounties on Lernęki. Living off the troves of Dewclaws.”

There was a skittering sound overhead, and a few pinpoints of dust fluttered down from the vaulted rafters. None of the listeners looked up, but Lukasz’s focus shot to the chandelier and the shadows beyond. A wisp of smoke, scarcely larger than a cat, rolled across the rafters and disappeared into darkness at the far end of the hall.

He relaxed. Just a dola. Nothing more.

Lukasz settled back against the doorframe, watching Bieleć through the hazy air.

“And then,” continued Professor Bieleć. His knuckles were white on the lectern. “The brothers arrived in the town of Saint Magdalena, where for three hundred years, a Faustian had terrorized the countryside.”

The slide changed again. Amid the wreckage stood a man and a boy. A Faustian dragon sprawled behind them. This photograph had been taken among the ruins of a cathedral—now nothing more than splintered pews, shattered glass, and scorched stone. So fresh was this kill that its antlers had not yet fallen, and its still face was crowned with glittering, staglike horns. . . .

Darkness tipped one of the tines.

The man in the photograph was tall. He was handsome and hawkish, smiling and savage in leather and fur, broadsword strapped across his back. He beamed, like a proud father, arm around the boy, as if congratulating him.

Lukasz knew better. The man was holding the boy up on his feet. It did not show up in the monochrome photograph, but the boy’s pant leg was soaked through with blood. At the memory, pain stabbed through his knee.

On went the professor.

“The last of the Wolf-Lords.” The professor’s voice fell to intonations usually reserved for worship. “Their exploits are chronicled in photographs and newsprint. But we know so little of who they were. Of how they must have felt—how lonely they were—the last of their kind in a world like ours.”

The slide changed. The brothers in one of Kwiat’s famous bathhouses, cast in shadow by flames burning in the stone pool behind them. The image shuddered, disappeared, was replaced. Brothers standing on a dock, while behind them a pair of Tannimi hung nose-down from cranes like enormous, grotesque salmon. A click, and a new image appeared. Brothers smoking with swords propped on their shoulders, a Ływern stretched out across the cobbles beside them. As the photographs changed, the brothers changed: from leather and fur to sleek black uniforms, from wild beards to fashionably short hair. From savages to celebrities, each moment captured. Immortalized on celluloid film, even if they were dead.

As the slides changed, Bieleć’s voice became hushed and hallowed.

“Bound together by blood, by fire, by the loss of the world they’d left behind and the fear of the world they’d entered. Cursed, lonely, destined for the outskirts of civilization. By tooth or by claw, they promised. The Brygada Smoka. The last of the Wolf-Lords, and the greatest dragon slayers in the world.”

The whole room held its breath, with the exception of Lukasz. Then again, he thought, perhaps this is worship.

Lukasz glanced down at his hands. Realized, a little distractedly, that he’d forgotten his gloves. When he looked up again, the slide had changed once more.

The last pair of Smokówi brothers smiled for the camera. They wore black army uniforms trimmed in silver braid and gleaming with medals. One had spectacles and artistically messy hair that did nothing to soften the brutal slant to his cheekbones. The second man was younger, with black hair and eyes whose blue had evaded the colorless camera flash. All the same, they had a wicked glint.

Lukasz knew those eyes very well.

They were his.

“But then,” whispered Professor Bieleć. He spoke, it seemed, into Lukasz Smoków’s very soul. “But then the Brothers Smokówi began to disappear.”

Lukasz waited for the auditorium to empty before he strode to the front of the room, where Professor Bieleć was folding his notes into a briefcase.

Lukasz could feel the Apofys in his bones. He’d spent the morning reciting its curriculum vitae: the demonic taxidermy collection devoured, the pagan amulet exhibition plundered, and four Unnaturalists gutte

d. And Damian Bieleć, newly promoted department chair. By default.

“Dewclaws don’t have troves,” observed Lukasz, snuffing out his cigarette in an ashtray. “Only bits of metal and trash.”

Bieleć shot bolt upright. Up close, he did not seem quite as impressive. He was small and pale and, without a podium or a captive audience, even a little pathetic. He’d probably escaped the dragon because he simply wasn’t very appetizing.

Bieleć took in everything from the black army cap on Lukasz’s head to the tall leather boots.

“L—Lieutenant Smoków—” he began. “I didn’t realize—”

While Bieleć gathered his wits, Lukasz licked his fingertips and reached into the projector to snuff out the gaslight. He didn’t mind the tiny sear of pain. If you hunted dragons, you got used to burns.

Lukasz interrupted:

“Heard you’ve got an Apofys on the loose.”

Bieleć wiped sweaty hands on his elegant suit, eyes running down to the old-fashioned broadsword at Lukasz’s side. What was it Eryk used to say?

Lukasz remembered the eyes, darker than mountain skies. The laugh, easier than a falling blade. Teeth brighter than dragon bones.

Dress us like gentlemen, and we’ll hunt like wolves.

“Aren’t there two of you?” Bieleć was asking. “It’s really quite a dangerous creature—”

Hand still in his pockets, Lukasz fiddled with the cap of the lighter.

“You want it dead or not?” he cut in. “Just show me where to find it.”

“Well—it’s—” Bieleć struggled. “Well, it’s in the department of Unnatural history. You should be able to find it. The hallways are very clearly labeled, and we’ve even put up a sign—”

For a second time that afternoon, Lukasz felt uneasy. Maybe Franciszek had been right after all, about that whole reading thing.

“I’d rather you showed me,” he interrupted as casually as he could. “Just as far as the department. After that, it’ll find me.”

Bieleć blanched.

“Well . . .” He hesitated. “Very well, I suppose. Could you take this, please?”

Lukasz took the briefcase and the projector and followed Professor Bieleć out of the auditorium. They moved in silence through the uniwersytet’s lobby. It had the kind of richness designed to make a man like Lukasz feel small: an enormous gold globe to his left, a mural of the country’s founding covering the entire wall on his right. Jarek would have loved that mural. A wide pink velvet carpet ran from the auditorium doors to a white stone desk inlaid with gold lettering. Two clerks, one male and one female, each of astounding beauty, sat behind it. And flanking either side of the desk, twin white staircases curled up to a second story, which promised more velvet and gold.

Don't Call the Wolf

Don't Call the Wolf